Walls, Martyrs, Merchandise: Welcome to the Border Theme Park

Text and photos by Lennart Schmidt, May 2025

Anyone who was a student in West Germany during the 1980s likely recalls the obligatory class trip to West Berlin, which invariably featured one key activity: visiting the Berlin Wall. Whether standing in a viewing platform at the Brandenburg Gate or in Potsdamer Platz, students could glimpse the other side of the city, wave at East Berliners, and simultaneously feel the stark reality of division. For West German students, the deadly boundary for East Germans became a curated experience space. It was an early example of what is today referred to as border tourism.

Borders – symbols of separation and control – have become tourist attractions in some places. The demilitarized zone (DMZ) between North and South Korea or the highly surveilled border between the USA and Mexico now draws hundreds of thousands of visitors annually. One of the most spectacular examples, however, is the daily ritual at the India–Pakistan border near the northern Indian town of Wagah. Since the late 1950s, a patriotic border performance has been staged here every evening – a choreography of military pageantry, emotional fervor, and national pathos that feels more like a pop concert than a state ritual.

Even the journey to the site feels like a fairground: From nearby Amritsar, the capital of Punjab, one travels about 30 minutes in a shared rickshaw to the border. From there, it’s a short walk past countless vendors selling anything that can shimmer in the Indian tricolor – flags, pajamas, makeup, bracelets, or caps. The path leads to a semicircular stadium, reminiscent of the size of Champions League football arenas, with one key difference: one-half is missing. The smaller half sits on the Pakistani side, separated by a massive barbed-wire fence.

What follows is a carefully orchestrated display that combines parade, performance, and political maneuvers: while an officer from the Indian Border Security Force (BSF) rallies the crowd with chants, selected women from the stadium audience wave national flags as they dash back and forth along the parade route. Meanwhile, a one-legged Sufi dancer spins joyfully on the Pakistani side in circles. Ultimately, soldiers from both sides march forward in unison, lifting their legs into the air, stomping, saluting, and glaring at one another—a disciplined duel cheered by spectators. After two hours, the event comes to a close. The stadium gradually empties, leaving behind the understanding that this commemoration signifies not only a border but also a national story being performed.

View of the border and the Pakistani border stadium behind the barbed wire shortly before the parade begins: While the Indian stadium holds around 24,000 spectators, its smaller Pakistani counterpart seats about 5,000 – but features a taller flagpole and a highly visible national flag.

What follows is a precisely choreographed sequence between parade, performance, and political power play: while an officer of the Indian Border Security Force (BSF) fires up the crowd with chants, women waving the national flag dance to Bollywood beats and patriotic songs toward the fence. On the other side, a one-legged Sufi dancer spins ecstatically in circles. Finally, soldiers from both sides march up, throw their legs into the air in sync, stomp, salute, and stare each other down – a duel of discipline cheered on by both sides. After two hours, the spectacle ends. The stadium empties, and what remains is the insight that what is being marked here is not just a border, but a national narrative being staged.

Wagah is no longer an exception. The Indian government has recognized the symbolic value of such sites and is investing heavily in their touristic upgrade. One striking example can be found in the salt desert of the Rann of Kutch in Gujarat. Under the label of “Battlefield Tourism”, a place has emerged that defies traditional categories: part theme park, part museum, part art gallery, part war memorial – a patriotic complex focused on India’s border history, designed to combine emotional education with family-friendly entertainment.

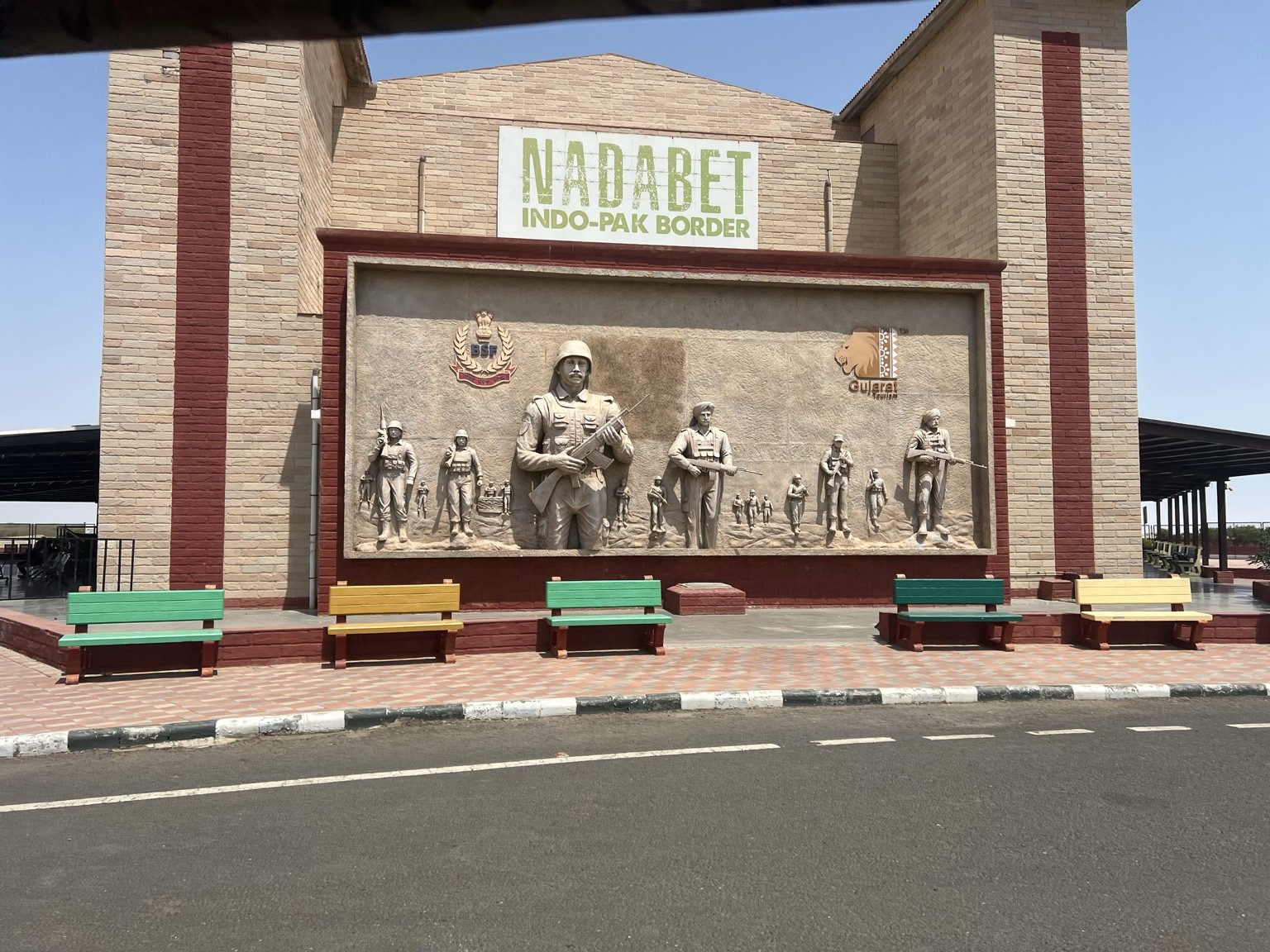

One of the exhibition buildings in the Nadabet Border Park features a mural of the Indian Border Security Force (BSF).

One of the exhibition buildings in the Nadabet Border Park features a mural of the Indian Border Security Force (BSF).

Funded by India’s Ministry of Defence and the national tourism authority, this “border theme park” is meant not only to preserve historic sites but also to promote national pride. Former Chief of Staff V. K. Singh put it like this:

“Battlefield tourism in India offers a unique perspective on the country’s history, culture, and patriotism. Each experience is a journey into the heart and soul of the brave soldier who stood proud, fought, and died for the nation.”

Nadabet is a striking example of this emerging culture of remembrance. Visitors move through a carefully choreographed experience space where they don’t just learn about India’s border forces – they can embody them. You can steer a replica patrol boat through a synthetic river delta, simulate surveillance of the India–Bangladesh border, or wear a VR headset to patrol the India–Pakistan fence yourself – an immersive encounter designed to generate identification with the nation through interactive experiences.

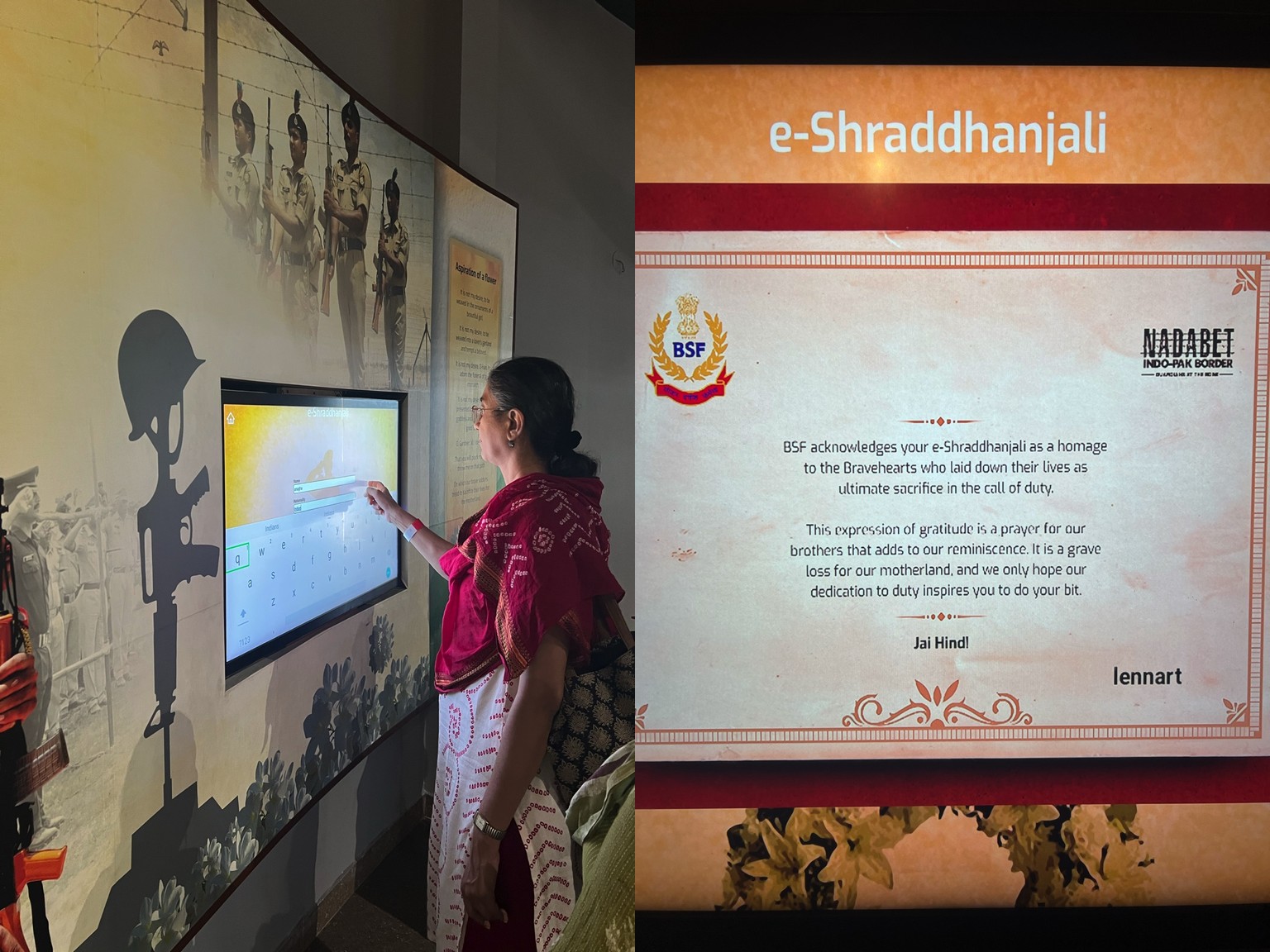

A visitor enters her name for the E-Shradhanjali. Afterwards, one receives a personalized certificate from the Indian Border Security Force.

A visitor enters her name for the E-Shradhanjali. Afterwards, one receives a personalized certificate from the Indian Border Security Force.

There are also contemporary art galleries exploring the theme of “borders,” and memorials commemorating the martyrdom of Indian soldiers during the third Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. Here, visitors can leave a so-called E-Shradhanjali – a digital tribute entered via touchscreen, which generates a personalized certificate you can photograph and share online. Memory, selfie, and patriotism – all in one package.

The final highlight is a visit to “Point Zero,” the actual border fence in the middle of the desert. Until recently, international tourists were not permitted here, though a park official jokingly told me I wouldn’t miss much – after all, “it’s really just a bit of barbed wire in the middle of the desert.”

Borders as Staged Society

Sites of separation, distrust, and violence are increasingly also becoming stages of patriotic performance, collective remembrance, and commercial entertainment. The border isn’t being dissolved, it’s being reinvented: as an immersive space, as a projection screen for national identity, and as a commodified spectacle.

Border tourism in India and beyond moves in a tension between education and commodification, between memory and glorification. What’s offered as an opportunity to engage with history often turns out to be a tightly controlled narrative that produces not critical reflection, but patriotic pathos.

So the question remains: What do we see when we visit a border – and what are we not supposed to see? Is history being told here, or merely staged? Is this about memory or elevation, reflection or reproduction of national myth?

Borders don’t just mark where a country ends – they reveal how a nation sees and stages itself. To visit the border is to move through the narratives of a nation. This is why it’s worth not just following the script, but reading between the lines, searching along the fence, and beyond the merchandise, for the story that often begins where the official message ends.

In addition to the museum-like and performative presentation of physical borders, a digital expansion is evolving, most notably in India. While Wagah and Nadabet provide military rituals, immersive entertainment, and memorial technology such as E-Shradhanjali, there is a simultaneous transition occurring: moving from visible barriers to invisible systems of control governed by algorithms.

At the core of this transition are two programs: the biometric ID system Aadhaar and the airport travel initiative Digi Yatra. These programs demonstrate that today’s borders are defined not by fences or checkpoints but by data flow, scans, and digital identity management.

Established in 2009, Aadhaar is the largest biometric registry globally. It gathers iris scans, fingerprints, and personal details of over 1.2 billion individuals, becoming essential to India’s administrative framework, from welfare access and tax identification to SIM card registration. The database marks a turning point in India's long history of computing. Ostensibly, its goal is to boost efficiency and minimize “leakages” in public services. However, the reality is mixed: authentication errors often exclude individuals, particularly from disadvantaged communities, from crucial benefits. Additionally, there have been significant data breaches, such as incidents where the information of over 81 million citizens was allegedly sold on the dark web.

Another example is Digi Yatra, a facial recognition system launched in 2022 at Indian airports. It enables registered passengers to navigate security without presenting IDs or boarding passes, relying solely on facial scans. While it offers convenience and modernization, critics highlight concerns regarding transparency: many travelers recount feeling pressured or misinformed about the registration process. Although the data is intended to be erased within 24 hours, one study indicates that this does not necessarily extend to metadata and movement profiles.

The emotional mobilization at the border is now accompanied by a digital infrastructure that defines belonging in a technocratic fashion. Aadhaar, Digi Yatra, and analogous systems extend the border into the invisible realm of databases, interfaces, and government backends. The border transcends being merely a physical line drawn in the sand or indicated by a fence; it is now encoded in software and enforced by algorithms.